The transaction outlined in the secret Goldman file would have been the culmination of an ambitious proposal to salvage Michael Jackson’s crumpled financial life. Jackson owed $270 million to Bank of America, which could take control of his songs had he missed a looming due date.

Under the Goldman proposal, he’d forfeit the music — an outcome that he fiercely wanted to avoid — but emerge with a horde of as much as $1.3 billion.

The confidential files from those days were provided by a member of the Goldman Sachs group, which grew out of a chain of relationships started by “Rush Hour” director Brett Ratner in late 2002. (Click on documents to enlarge.)

Acting as Jackson’s adviser, Charles Koppelman, the veteran entertainment executive and investor, recruited Goldman Sachs and worked closely with two of its private-equity aces, Gerry Cardinale and Henry Cornell, in crafting the proposal.

Acting as Jackson’s adviser, Charles Koppelman, the veteran entertainment executive and investor, recruited Goldman Sachs and worked closely with two of its private-equity aces, Gerry Cardinale and Henry Cornell, in crafting the proposal.

Ahead of the proposal, he and Florida businessman Al Malnik also arranged to double — to $70 million — one of Jackson’s two loans with Bank of America, where a Koppelman friend, Jane Heller, happened to handle his and Jackson’s personal accounts.

See the full document: Jackson’s $70M Loan

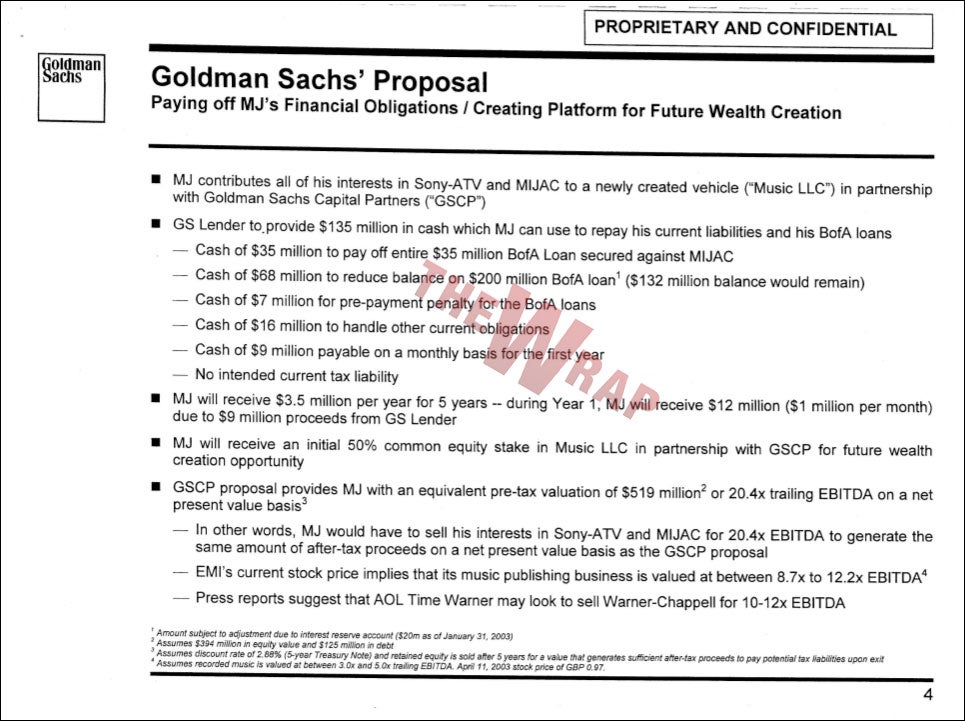

The confidential Goldman documents detail a proposal with several steps:

>> First, Goldman and Jackson become 50-50 owners in a new company, Music LLC.

>> Next, Music forms a separate company, “Newco,” with new partners — Sony, with its half of the Beatles, and Goldman putting up money.

>> Newco’s assets would be 100 percent of Sony/ATV (the Beatles) and Mijac (Jackson’s hits) and Goldman (more cash).

>> Newco would swallow Warner Music Group’s music publisher, Warner-Chappell, and combine it with Sony-ATV.

>> Newco would swallow Warner Music Group’s music publisher, Warner-Chappell, and combine it with Sony-ATV.

See: Goldman’s Secret Rescue Plan and The Term Sheet

A target list also included other publishers — arms of Universal Music Group, BMG or EMI. The goal: industry dominance.

Jackson’s original stake would shrink as more investors entered the Goldman-crafted venture. “Like Bill Gates, [Jackson] would have a smaller stake in a multibillion-dollar company,” Goldman declared in a talking-point memo dated April 15, 2003. (See: Michael Jackson = Bill Gates)

Within five years, Goldman’s typical time frame for such investments, all would have been monetized in a sale of the venture, most likely to Sony Corp. By Goldman’s projections, Jackson’s share would be $700 million to $1.3 billion.

But backend riches didn’t solve Jackson’s shorter term crisis of repaying the $270 million bank debt. Not to worry. A $135-million Goldman loan would retire the $70-million Bank of America loan and $7-million due Sony. He would catch up on $12 million in overdue monthly bills and have a few million as a cushion. (See: Jackson’s Goldman Loan)

Goldman planned to repay itself from Jackson’s backend bounty, but it was unclear how he’d repay the remaining $200 million bank loan. This much was clear, however: If he defaulted, Bank of America could legally force him to sell his share of the venture to Goldman, with the proceeds handed out to the bank. (See: Goldman Gets Michael’s Beatles, If …)

As Jackson’s putative partner, the Wall Street titan would have hogged much of the power: twice as many shareholder votes as Michael in their jointly-owned Music LLC and eight of 10 board seats — or seven if Jackson’s three picks included Koppelman, whom the secret documents show was as much a partner of Goldman as he was an advisor to Jackson.

As Jackson’s putative partner, the Wall Street titan would have hogged much of the power: twice as many shareholder votes as Michael in their jointly-owned Music LLC and eight of 10 board seats — or seven if Jackson’s three picks included Koppelman, whom the secret documents show was as much a partner of Goldman as he was an advisor to Jackson.

A Jan. 7, 2004, term sheet — drafted by Goldman’s lawyers at Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz — also granted the Wall Street bank “drag-along rights … to require MJ-ATV Trust” (with control over Jackson’s Beatles interest) to participate in the contemplated cash-out deal. Drag-along rights prevent a minority partner from sitting out a sale of the company — something Jackson was apt to try to do. (See: The Term Sheet)

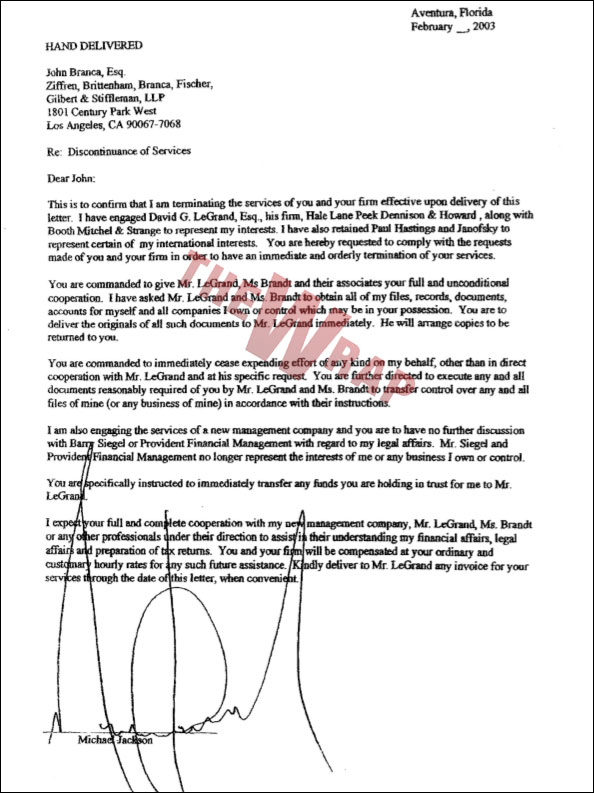

As the most far-reaching transaction of his career progressed on paper, Jackson wanted his long-time lawyer, Branca, nowhere in sight. “You are commanded to immediately cease expending effort of any kind on my behalf,” Jackson wrote him on Feb. 3, 2003, offering no reason for the firing. (See: You’re Fired!)

Yet, Branca hardly could be shut out, given a 5 percent interest in Jackson’s Sony/ATV stake. Branca would have pocketed $17 million from the dealings, Malnik said in a recent interview. In a letter to Koppelman on July 28, 2003, Branca underscored his financial interest in writing, to be passed on to Goldman. (See: Branca’s Secret Letter)

Yet, Branca hardly could be shut out, given a 5 percent interest in Jackson’s Sony/ATV stake. Branca would have pocketed $17 million from the dealings, Malnik said in a recent interview. In a letter to Koppelman on July 28, 2003, Branca underscored his financial interest in writing, to be passed on to Goldman. (See: Branca’s Secret Letter)

With his interest linked to Jackson’s, Branca seemed to have little choice but to be a zealous advocate for the entertainer. In case Michael wanted out of the venture, “an exit strategy needs to devised for [him] to receive fair market value.” Skeptical of Goldman’s power grab, he insisted that “Michael should have some control over the management and operation of the venture.”