Nikki Finke may be known as having chutzpah to spare, but Deadline’s lawsuit against The Hollywood Reporter goes where few newsrooms have gone before, demanding legal remedy for “stealing” its scoops.

In the internet age of aggregation, where the lifespan of an “exclusive” can be measured in seconds, attorneys say Penske Media Corp., Deadline’s parent, faces an uphill fight to make its lawsuit stick.

“You can’t stop the world from using information you report,” said Thomas R. Julin, a First Amendment specialist at Hunton & Williams. “But if [THR] is simply grabbing that in some mechanical fashion, taking it and republishing it as their own, there might be some tort.”

Also read: Why Nikki Finke’s Content Theft Lawsuit Is Interesting, If Still Batty

In a response to the lawsuit, THR released a statement that basically said, that’s how news gets reported around here.

“An initial review of the complaint shows that it is replete with examples of stories that originated from widely-released press releases from publicists, or widespread confirmations from publicists to numerous outlets, including both The Hollywood Reporter and Deadline.com,” went the statement. “It is not copyright infringement to report these stories, even if on occasion Deadline.com posts them first.”

Lawyers say that PMC cannot argue that it owns the news and instead must demonstrate that the Hollywood Reporter systematically parroted Deadline’s reporting without performing any independent verification.

Also read: Hollywood Reporter Calls Bull on Nikki Finke News Theft, Will Check on Copied Code

Finke's lawyers may implicitly recognize this fact, because the demand for $5 million in damages for copyright infringement is tied to the alleged theft of source code, rather than news content.

The suit lists dozens of stories where the Reporter's version was posted less than an hour after Deadline, and asserts that Reporter employees “continue to engage in a practice of closely monitoring Deadline’s website minute-by-minute for the specific purpose of spotting key news stories and original content and reproducing them.”

That alone is not sufficient evidence to win a copyright infringement case, say the experts.

To prove its claims, Penske will have to conduct discovery, which would entail extensive research into how the Reporter collects its information.

Also read: Nikki Finke to THR: 'Get the F— Out of My Face'

That could then give THR an opportunity to inspect Deadline’s operation — which the secretive Finke would probably be loath to permit.

Over decades media companies have rarely taken their gripes about stealing scoops into court, so there is little legal precedent for Penske's attorneys to draw on.

Since the internet revolution, there have been only a handful of court cases and none of them have done much to clarify the difference between aggregating and outright theft.

One landmark case was The Associated Press v. All Headline News Corp., which advanced the so-called “hot news” doctrine. That law restricts news organizations from unconstrained lifting of reporting done by competitors. (The aggregator settled the case with AP.)

But a more recent case complicated the picture, as a court ruled in favor of financial newswire service flyonthewall.com, arguing that banks could not stop the site from immediately reporting on analysts’ recommendations. The distinction here is that a site cannot reprint someone else’s content, but it can report on that content.

Neither of these cases provide a clear legal framework for Deadline, which uses legal terms like “free ride” that are associated with the hot news doctrine, but cites no legal precedents.

The “free ride” reference is usually used to prevent companies from reproducing and profiting off another site’s reporting without investing in their own newsgathering. That, the thinking goes, unfairly puts competitors at a financial disadvantage.

“Form the perspective of the courts, if you allow companies to exist parasitically off of other people’s newsgathering they’ll go out of business,” said Andrew Deutsch, an attorney at DLA Piper, who also worked on The Associated Press and flyonthewall.com cases.

However, even proving that is quite a challenge.

“For the law to intervene, it has to be in someone’s business model to not hire reporters and to copy other sites content and copy it all the time,” Deutsch added.

THR, like many other sites, may be in the business of aggregating, but it has its own reporters and much of its content is original. Even two of the stories cited in the suit exhibit original reporting from a THR employee.

None of its stories give any credit to Deadline for its original reporting, but legal experts do not seem to believe that is enough to demonstrate copyright infringement, particularly as the stories in question focus on factual minutiae such as release dates and executive reshuffling.

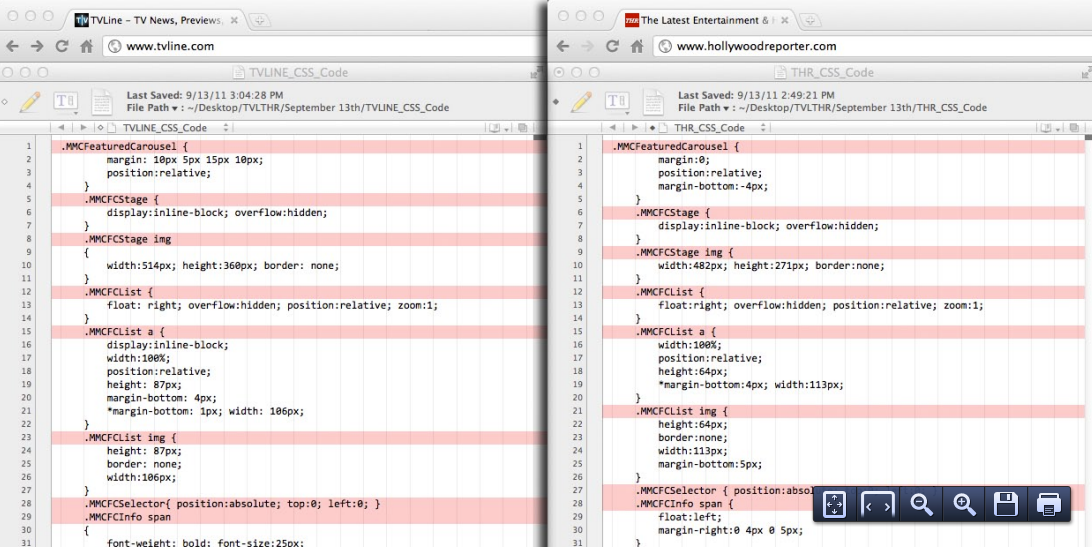

Penske's case may more solidly rest on allegations that the Reporter's spiffy new home page directly lifted coding from its TVLine.com. THR has already removed one of the designs in questions from its site, and said it would investigate the allegation.

“There’s a huge disparity in the strength of their claims,” said Shyam Balganesh, professor of law at University of Pennsylvania.

Though Penske took the steps to copyright that coding, according to the suit, it is common practice for web developers to borrow liberally from other JavaScript sites. Of course, the same goes for aggregating content.

Common practice, in the case of web development, may still be illegal.

That means Prometheus may be writing a check to Jay Penske even if a court decides that THR did the leg work to confirm that “Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol” would indeed be released in time for Christmas.