I was shocked, when I realized that I had forgotten about Burma.

How could an entire country vanish from consciousness? The country’s military regime had an obvious interest in keeping the country closed and "forgotten," but how was it possible for them to succeed so well in today’s globalized society?

It was at the end of 2004, before the Saffron Revolution, before the cyclone and before an American decided to swim across a lake to visit Aung San Suu Kyi — events that caught the attention of world media. Jan Krogsgaard, a Danish video artist living in Asia, approached me with the idea to make a film about Burma, and I immediately knew that I had to.

It was at the end of 2004, before the Saffron Revolution, before the cyclone and before an American decided to swim across a lake to visit Aung San Suu Kyi — events that caught the attention of world media. Jan Krogsgaard, a Danish video artist living in Asia, approached me with the idea to make a film about Burma, and I immediately knew that I had to.

We started developing the film, and Anders Østergaard, an established Danish documentary director, came on board. There were many touching human interest stories in the shape of refuges and victims of abuse, but we did not want to film "the results" of oppression — we wanted to focus on the oppression itself.

But how to capture everyday oppression on film when nothing much happens and people are afraid to talk to you? And how do you make a portrait of a regime if you are not allowed inside its country?

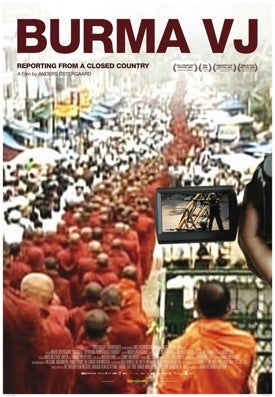

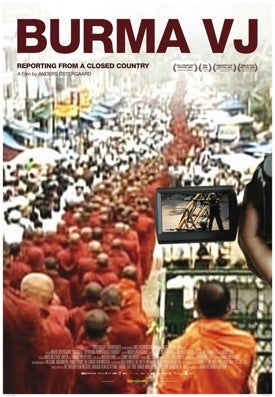

Some six months into development, we learned that Democratic Voice of Burma (by then a radio station in exile) had received seed funding to start producing and broadcasting TV into Burma via satellite. They were to train undercover video journalists to make reportages from inside Burma. Their tapes would then be smuggled out of the country, sent to Oslo, edited, and broadcast back into Burma via satellite.

For the first time, the Burmese people would be able to see reportages and news pieces about themselves that was not part of the regime’s propaganda machine. It was an intriguing thought. The journalists were central to fighting the military’s information lock down – and if we were able to cooperate with them, they could also be our eyes and ears inside the country.

To make a long story short: DVB agreed to cooperate with us, and we found a main character in the shape of a young journalist working with them. However, 18 months into the film’s development he had to emigrate — not an unusual fate for people working illegally — and we were back at square one. I did consider momentarily giving up but could not.

So we started all over again, researching for a new main character.

The VJ’s (video journalists) have to work in very small units, because if one is caught, he will be tortured and eventually spill what he knows. Because of the risks the undercover journalists run every day, we had to meet them outside the country, and we had to develop a method by which our main character could be the point of identification, yet never be seen on screen.

Meeting Joshua was a very decisive moment. He was so young, so bright, and so determined, and he wanted to work with us. He was the perfect representative of the VJ’s, with his very unusual combination of extreme courage and extreme humility and patience.

His primary motivation was to promote change by bringing his country out of oblivion, but at this point in early 2007, nothing out of the ordinary happened in Burma. The footage was scarce and not very poignant, so we focused on the existential question: What made Joshua (and other VJ’s) continue their hazardous work with no obvious result or reward?

Then in August 2007, after two shooting periods and a sense that this would be a short psychological portrait of a VJ, we suddenly sensed that something was about to happen in Burma and quickly adapted our strategies, rushed to raise more financing and planned a new shooting period — incidentally almost coinciding with the Saffron Revolution in late September 2007.

These were extremely emotional days. History was happening in front of our eyes — but at what cost? Would the uprising be successful? What would happen to the VJ’s if not? How much would they be able to document?

The way the VJ’s operate is this: Every time they manage to secure a few minutes of footage, they take the tape out of the camera and hand it over to somebody else, who tries to smuggle it out of the country or upload it. Joshua had had to leave the country just before the uprising, and now coordinated the VJ’s from abroad and spread their material to CNN, BBC and other news channels around the world. His group was among the very last to be able to obtain and send material out of the country.

After the government’s crackdown, the network was in shambles with VJ’s imprisoned or in hiding, and footage scattered. Nobody had any kind of overview as to what footage had been captured, rescued, lost, or hidden. We searched for material in December and January with the help of DVB and the networks we had established. By the end of January, we had obtained roughly two hours of material and thought that it was all there was. So we decided to start the editing and planned one additional shooting period.

A few weeks into editing, undercover material started trickling in from many different sources, and by the end of May, we suddenly had some 60 hours of material with no identifying info attached. We might get a 30-second clip in February which turned out to be a direct continuation of a 60-second clip we later received in May.

With the help of Google Earth, which has quite detailed images of Rangoon, our editor was able to identify the streets and houses in the various clips, and use the weather conditions, light, direction of the marching monks, the size of the crowd etc to meticulously reconstruct what actually happened and how the clips fit together.

Of course this completely ruined our post-production schedule and made our budget explode (again), but it also gave us a very strong feeling of obligation to continue, as we had become the only ones in the world with access to a comprehensive visual record of the Saffron Revolution and the ability to bring it out.

From a production point of view, the project was extremely challenging until the obligation to history and the creative and artistic aspirations for the film came together. It is immensely satisfying to know, that had we not been making this film, most of this completely unique material would have never seen the light of day.

The VJ’s were focused on delivering news clips to global media. Since the vast majority of clips from the Saffron Revolution did not surface until they had long lost their news value, most of the material would have been scrapped.

Just as the VJ’s have been an immense inspiration to us, they tell us that they have learned a lot from the way we work. When Burma VJ received the Grierson Award in the U.K. this autumn, some of the new VJ-recruits simultaneously were awarded the Rory Peck Feature Award for their film on the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis. Not only have they started working in new ways, they recently have received additional funding and political support.

When we started working on the film, there were some 25 journalists working undercover. When the Saffron Revolution ended, the network was in shambles, but one year after the release of the film, there are over 80 new undercover journalists working to keep Burma from oblivion.

Our Burmese contacts tell us, that the Oscar nomination has refueled the motivations and resolve of the peace and freedom movement inside Burma, and that they feel that it is a recognition that will help draw attention to their cause.

Let’s hope it will do just that.