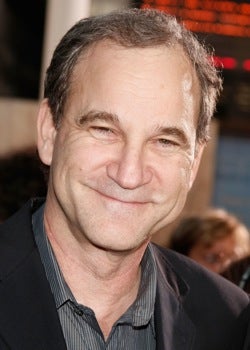

Marshall Herskovitz burst onto the cultural scene in 1983 with the television movie “Special Bulletin,” whose realistic treatment of cataclysmic fictional events made the apocalypse almost matter-of-fact, then cemented his place in TV history with “thirtysomething,” which could make personal, everyday occurrences seem like the end of the world. He also has won acclaim in features, including an Oscar nomination he shared with longtime partner Ed Zwick for “Traffic.” He is a third-year president of the Producers Guild of America, which this weekend is mounting its sold-out Produced By conference at Sony headquarters in Culver City.

Herskovitz talked with Eric Estrin about his rude introduction to Hollywood, gambling on himself — and launching a hit series despite trying to fail.

After I graduated from Brandeis, I took all the money I had in the world, which was $5,000, and I made a short film. I made every mistake you could possibly make. It was a total disaster as a piece of work, and yet, you know, it was ambitious in some way.

It took me a year to finish it, and in 1975 at the age of 23, I moved to California with every intention of being instantly hailed as the next great director. Of course, I literally couldn’t get anyone to look at it. In those days, all you could do was go through the Yellow Pages and try every production company — they all said no.

It took me a year to finish it, and in 1975 at the age of 23, I moved to California with every intention of being instantly hailed as the next great director. Of course, I literally couldn’t get anyone to look at it. In those days, all you could do was go through the Yellow Pages and try every production company — they all said no.

So I ended up begging my father to help me out, so I could attend the American Film Institute. It really changed my life. I was there as what they call a directing fellow, and my classmate was Ed Zwick — that’s where we met. It was his first day, and we became best friends. I got my first job as a writer while I was still at AFI through contacts I made there, so it was a classic Hollywood story. It’s all about who you know.

I began by going from show to show, barely making a living, writing other people’s episodes — which I didn’t think I was particularly good at. It made me miserable. I felt that I was gonna go nowhere and that I had to show the world my own voice. And so I made a decision that I was not gonna do that anymore. I would just stop, and I would sit down and write a spec script that would be mine, that it would show the world what I could do. The result, a year later, was “Special Bulletin.”

That decision was what made everything happen after that. In fact, when we went to pitch “Special Bulletin,” if I had said I’d only written episodic, they would never have allowed me to write that script. The fact that I had a longform script to show them, which they loved, enabled me to do that job. So it was a decision to gamble everything on my own that enabled that opportunity to take place.

“Special Bulletin,” put us on the map. We won four Emmys and every possible award and, you know, we were just two nobodies who had just walked into this astonishing reaction to that film.

“Thirtysomething” came a couple of years after that and as a direct result of it, because both of us had such a high profile at that point. We were offered an overall deal in television by David Gerber, who was running MGM television at the time, and it was directly as a result of “Special Bulletin.”

We thought it would be a great idea to work in television and we took the deal, but actually, we weren’t very interested in doing a series. We saw ourselves as filmmakers; we wanted to do miniseries, movies, things like that.

So “Thirtysomething” was an attempt to fulfill the literal terms of our deal, because we had to try to sell a television series, but we were hoping to fail. What we thought was, If we have to do a series, let’s at least do something that we can love and that no one will watch so it’ll be canceled very quickly.

That’s really what we thought at the time. And we thought that “Thirtysomething” would do it because it was so specific in its sensibility and its voice. You know, you saw personal movies, but not television shows. So we thought fine, we’ll soon go back to making movies.

Of course, that personal voice turned out to be the reason for the show’s success.