At a time when the independent movie business is in disarray and the industry is pinning its hopes on 3D, sequels, remakes and comic-book franchises, can there really be a place for avant garde cinema?

Sure, says director Chuck Workman, whose documentary about experimental cinema, “Visionaries,” screens this Thursday and Friday at the Seattle International Film Festival.

“There’s always been an audience for experimental film, and it’s still there,” says Workman (left), whose film also has special screenings at the Anthology Film Archives’ 40th anniversary celebration in New York June 4-6, and then the Chicago Underground Film Festival later in the month.

“There’s always been an audience for experimental film, and it’s still there,” says Workman (left), whose film also has special screenings at the Anthology Film Archives’ 40th anniversary celebration in New York June 4-6, and then the Chicago Underground Film Festival later in the month.

“And I also think there’s an audience among people who don’t know experimental film, but would enjoy it if they saw it.”

If Workman doesn’t see any problem reconciling the mainstream and the avant garde, it may be because that’s what he himself has done.

He’s made films about counter-cultural subjects (the Beat poets, Andy Warhol) at the same time that he’s assembling widely-viewed film packages for the Oscars every year, and working on films that would have been used prominently in Michael Jackson’s “This Is It” concerts if the pop star had lived.

“I was working on ‘Visionaries’ at the same time that I was working for Michael Jackson,” says Workman, who won an Oscar for the short “Precious Images” in 1986. “One fed off the other, somehow. Of course it’s a different audience, but I’m not backing away from either of them – I’m fully interested in them both.”

Certainly, underground film can have an impact on the mainstream in different ways. The film awarded the Palme d’Or by Tim Burton’s jury at Cannes Film Festival this week, “Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives,” was by all accounts the most challenging and experimental film in the entire competition; meanwhile, this year’s Best Director at the Oscars, Kathryn Bigelow, is a former art school student who was drawn to become a filmmaker by the experimental, transgressive cinema of directors like Kenneth Anger and Pier Pasolini.

Anger is one of the subjects of Workman’s film, along with the likes of Stan Brakhage, Ken Jacobs and Jonas Mekas, whose stewardship of the Anthology Film Archives gives the film its subtitle: “Jonas Mekas and the (Mostly) American Avant Garde Cinema.”

The film grew out of an initial afternoon of taping that Workman did with Mekas, which led to an increasing interest in the filmmakers whose work was preserved by the Anthology. “It started out as a small homemade movie, but it turned out to be a real movie,” says Workman, who paid for the tiny budget out of his own pocket.

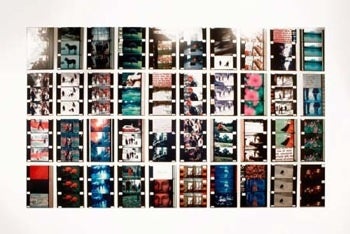

Partly, he could do that because the 100-plus film clips from avant garde films (by the likes of Brakhage, Anger, Warhol, Luis Bunuel and many others) were given to him free of charge by the filmmakers, at least while “Visionaries” sticks to the festival circuit.

The only two exceptions, he says, were Werner Herzog, whose company asked for “a fortune” for the rights to clips from the experimental documentaries the filmmaker made early in his career, and Robert Frank, who asked Workman to take out a clip from a film he shot with Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg.

In reviewing the film at Tribeca, Frank Scheck in the Hollywood Reporter wrote, “With 3D comic book franchises pounding even more nails into the coffin of independent movies, Chuck Workman’s ‘Visionaries’ seems more important than ever … The film, which received its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, no doubt will become a mainstay of university film courses.”

In reviewing the film at Tribeca, Frank Scheck in the Hollywood Reporter wrote, “With 3D comic book franchises pounding even more nails into the coffin of independent movies, Chuck Workman’s ‘Visionaries’ seems more important than ever … The film, which received its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, no doubt will become a mainstay of university film courses.”

But can it have an appeal beyond the halls of academia? “I think people who don’t know experimental film will enjoy it,” Workman insists. “Sure, people make fun of these kind of movies, but the film says to the audience, ‘I know you’re not idiots.’ It’s like poetry versus prose – if mainstream films are prose, these films are poetry.”

And if you presume that the poets behind these films have no interest in traditional Hollywood films, the director says that’s not the fact at all.

“A lot of these guys love to go to Hollywood movies,” says Workman. “Ken Jacobs said ‘Pineapple Express’ was his favorite movie last year. Stan Brakhage used to go to movies after work in Boulder, where he lived. He’d just go to a multiplex, walk into whatever looked interesting, watch for about 20 minutes and then walk into another movie.

“And the funny thing is, I do the same thing. When I want to catch up with the big Hollywood stuff, I just go into a multiplex and walk around. You miss the stories, but you can see what the movies are like.”

(Workman photo: AMPAS. "Visionaries" still courtesy Calliope Films.)