"Lost" began life as ABC's attempt to capture some of the magic of Mark Burnett's Darwinistic reality phenom "Survivor." It's ending its run as something far grander.

Put plainly, "Lost" will go down as one of the most important scripted shows to emerge from the millennium's first decade — and a template for what broadcast networks need to do to survive the new world order of unlimited viewing options and decreased ad revenue.

With the final season of "Lost" kicking off Tuesday, TheWrap tallies up five ways "Lost" changed the game:

— IT MADE IT POSSIBLE FOR A TV SHOW TO DIE WITH DIGNITY

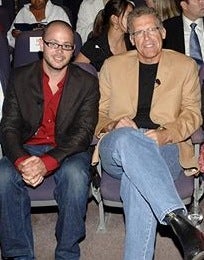

Letting showrunners Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse (left) put an expiration date on the series back in 2007 was brash, ballsy — and a complete paradigm shift for network TV.

Letting showrunners Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse (left) put an expiration date on the series back in 2007 was brash, ballsy — and a complete paradigm shift for network TV.

Pre-"Lost," programmers in the network world operated under the Supreme Directive that longevity was the end all, be all. Change the cast, shift showrunners — but damn it, once a show clicked with viewers, keep it on the air by any means necessary.

Lindelof and Cuse (known by Internet groupies simply as Darlton) knew that rule was a recipe for the creative implosion of "Lost." The storytelling had become too complicated, the entire premise of the series too narrow to support an open-ended run.

If "Lost" were to be a show for the ages, a series that lived on in other ways 20 years from now in the same way "Star Trek" has survived, it simply couldn't be allowed to linger on indefinitely, all of its mysteries hastily wrapped up six months after some future ABC suit declared it was time to move on.

And so producers began lobbying ABC to declare a certain date for the end of "Lost." The network agreed, wisely realizing that less of a great thing was better than more of an OK thing.

By limiting "Lost's" lifespan, Darlton gave fans a reason to stick by a show that was getting increasingly complex and in danger of losing all but its die-hard core. Ratings still fell, but like the Obama stimulus package, it's likely the decline would have been far worse had viewers not been given a reason to stay invested.

— IT PROVED THAT SERIALIZED STORYTELLING CAN BE GOOD BUSINESS

TV cynics will insist that procedurals such as "CSI" and "Law & Order" should always be the goal for broadcasters, since they repeat better and generally make more money in syndication.

TV cynics will insist that procedurals such as "CSI" and "Law & Order" should always be the goal for broadcasters, since they repeat better and generally make more money in syndication.

That's true — but "Lost" has shown that there's also a very healthy 21st-century business in high-quality dramas that require viewers to pay attention. Buzzworthy series such as "Lost" or "Heroes" or "Glee" help a network stand out amid the thousands of programming options out there for viewers, sparking online and mainstream media attention in a way the average procedural just can't.

What's more, syndication is no longer the slam-dunk payday it once was. Serialized shows also offer more opportunities for ancillary profits and have demonstrated far more appeal via electronic sell-through services such as iTunes.

None of this is to suggest that networks don't need a base of broad-appeal procedurals to thrive. But giving up on serialized shows just because they're tough to execute and offer less obvious financial upsides is equally foolish.

— IT NEVER UNDERESTIMATED ITS AUDIENCE

For decades, programmers operated under the assumption that the least objectionable programming made for the biggest success stories. That may still be true (four letters: "NCIS"), but "Lost" has shown that challenging fare need not be limited to cable.

Sure, there's no doubt "Lost" gave back more than a few eyeballs when it began delving deeper into mythlogy and moved away from the grown-up "Lord of the Flies" the series easily could have become. But what was sacrificed in terms of tonnage was replaced by something even more valuable to advertisers: an engaged, passionate audience that felt compelled to tune in every week.

Sure, there's no doubt "Lost" gave back more than a few eyeballs when it began delving deeper into mythlogy and moved away from the grown-up "Lord of the Flies" the series easily could have become. But what was sacrificed in terms of tonnage was replaced by something even more valuable to advertisers: an engaged, passionate audience that felt compelled to tune in every week.

The current issue of Entertainment Weekly has Darlton noting that they've been writing the show they wanted to watch, rather than the show they (or ABC) thought viewers wanted to see. By staying true to an artistic vision, and giving audiences credit for being able to handle something a bit more complex, "Lost" proved that networks could be both smart and successful.

"The TV business has become more like the movie business," former Disney chief Michael Eisner told Fortune just a few months after "Lost" premiered. "It's no longer the least objectionable program that wins the day. The excellent program wins the day."

— IT SET A NEW STANDARD FOR TV MARKETING

From the way ABC hyped the original pilot, to the carefully orchestrated campaign for the final season, marketing has been crucial in ensuring the success of "Lost."

One of the first big moves ABC boss Steve McPherson made when taking over the network was deciding to devote virtually all of his fall 2004 launch effort to just two shows: "Lost" and "Desperate Housewives." Instead of giving other newcomers like "Rodney" and "Life As We Know It" equal time, McPherson ordered the network's marketing team to focus like a laser on the network's prettiest babies.

One of the first big moves ABC boss Steve McPherson made when taking over the network was deciding to devote virtually all of his fall 2004 launch effort to just two shows: "Lost" and "Desperate Housewives." Instead of giving other newcomers like "Rodney" and "Life As We Know It" equal time, McPherson ordered the network's marketing team to focus like a laser on the network's prettiest babies.

It worked: Both "Lost" and "DH" opened big and became lasting hits. But to keep up the momentum, McPherson and his marketing team realized they needed to treat every new season of "Lost" as almost a sequel — complete with fresh ad themes and new hooks to lure in viewers.

Marketing also served a dual role in the case of "Lost." In addition to figuring out ways to let viewers know the show was on, ABC tried to make sure audiences kept up with what was going on — helping viewers track the increasing layers of mythology producers erected around the series.

Stunts such as "Pop Up Video"-style "Lost" repeats, stick-figure episode summaries and cell-phone webisodes kept viewers informed and engaged, even when the show wasn't on the air. And in some cases, they even generated revenue for the network.

— IT PROVED THE VALUE OF DEVOTED, FOCUSED SHOWRUNNERS

During TV's first 50 years, success in TV for executive producers was measured in how many shows they had on the air at any one time.

Norman Lear virtually owned CBS for a while. ABC became known as Aaron's Broadcasting Company during the 1970s, thanks to the prolific nature of the Aaron Spelling fluff factory. Ditto folks such as Steven Bochco, David E. Kelley and Jerry Bruckheimer during the last two decades.

Such producing promiscuity seems outdated, post-Darlton.

The two producers could have easily translated the early success of "Lost" into more pilots or series. Instead — with the financial support of ABC — they chose to stick with their baby throughout its entire life rather than go off and sire more offspring.

While there will always be non-writing producers such as Bruckheimer able to juggle multiple shows at one time, Dartlon have proven the value of obsessive, almost geek-like showrunners willing to go cradle-to-grave with a concept.