Documentary filmmakers are keeping a close watch on the Supreme Court.

Arguments in a new First Amendment case are scheduled for Tuesday, and the filmmakers fear that a ruling for the government could make it harder for the Michael Moores of the world to take on controversial subjects.

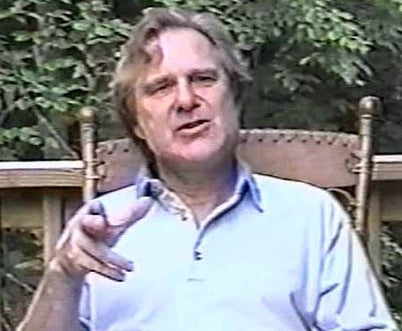

The case involves Robert Stevens of Pittsville, Va., a dog-fighting expert whose videography includes such titles as "Japan Pit Fights," "Pick a Winna" and what is now his best-known effort, the hour-long, "Catch Dogs and Country Living" (pictured).

In 2004, he became the first person ever prosecuted under a 1999 statute called the Depiction of Animal Cruelty Law because "Catch Dog" included a three-minute clip of a dogfight in Japan, where such activities are legal.

In 2004, he became the first person ever prosecuted under a 1999 statute called the Depiction of Animal Cruelty Law because "Catch Dog" included a three-minute clip of a dogfight in Japan, where such activities are legal.

The law represented Congress’ effort to halt the marketing of so-called "crush films," in which women wearing spiked heeled-shoes were shown impaling and crushing small animals to death.

Stevens (pictured below) did not film or have anything to do with the dogfight itself. He merely included the footage in his video.

A district court convicted him of animal abuse and cruelty. He was sentenced to 37 months in prison, 18 months more than NFL quarterback Michael Vick served for running a dogfighting ring.

But Stevens’ conviction was overturned when a divided appeals court refused to create an exception to the First Amendment that applied to cruelty to animals, striking down the law as unconstitutional.

The government is now asking the Supreme Court to overturn the appeals court ruling and treat depictions of cruelty to animals the same as child pornography, a request that is making documentarians nervous.

The government is now asking the Supreme Court to overturn the appeals court ruling and treat depictions of cruelty to animals the same as child pornography, a request that is making documentarians nervous.

"The threat to the film community is obvious when one considers films such as ‘The Cove’ and ‘Food, Inc.,’ to name two recent ones or ‘Roger and Me,’ to go back just a little ways," said Michael C. Donaldson, a Beverly Hills lawyer, speaking for four documentary-maker trade groups that joined in filing a brief in support of Stevens. "Certainly videos concerning hunting could fall within this statute, even though, as in Stevens case, the hunting was legal where the video was shot."

Indeed, in Stevens’ own response to the government’s appeal, he said the exception sought would jeopardize documentaries that show scenes of Spanish bullfighting and activities inside slaughterhouses, a vital part of the Richard Linklater’s 2006 film, "Fast Food Nation," based on the Eric Schlosser best-seller of the same name.

Donaldson said that a government victory would lead to many more exceptions to First Amendment protections, putting trial juries in the position of interpreting whether a portrayal of a controversial subject "with serious religious, political, scientific, educational, journalistic, historical, or artistic value," — as the law says — should be entitled to First Amendment protection or not.

"It’s a constant battle with First Amendment issues," he said. "So we support protections for the least popular subjects, the smallest and the weakest."

Donaldson’s four groups — Film Independent, the International Documentary Association, the Independent Film Project and the Independent Film and Television Alliance — are among several dozen organizations, including booksellers, theater owners, First Amendment lawyers and the National Rifle Association, that have filed briefs with the court, supporting Stevens.

Among the opponents is the Humane Society of the United States, which has urged the court in its own brief that the 1999 law should be upheld.

On his blog titled, "Animal Torture Is Not Free Speech," the Society’s CEO, Wayne Pacelle, said Monday that the law is "not only constitutional but urgently needed," pointing out that dog-fighting is a felony in all 50 states, anyway.

He said that since the law was struck down, sales of dog-fighting videos as well as crush films have surged.

"Cruelty to animals is a serious social and legal concern to Americans, and, as with children, the animal victims cannot defend themselves," he said. "There’s no speech at risk here — just the most appalling forms of cruelty known to humanity."