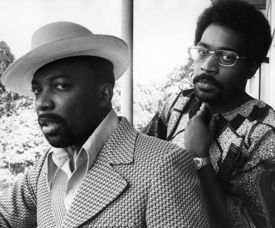

Songwriters, producers and entrepreneurs Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff set a message of love and togetherness to lushly orchestrated ballads and dance tunes to create the Philly Soul sound of the 1970s. Their Philadelphia International Records grabbed the baton from Motown and Stax in 1971 and quickly commandeering the pop and R&B charts with records by the O’Jays, the Spinners, Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, Jerry Butler, Lou Rawls and Billy Paul.

A decade ago, they received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy; in 2008, the 45th year of their partnership, they received the Ahmet Ertegun Award from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. On May 19, they will be named BMI Icons, given to artists who have a “unique and indelible influence on generations of music makers.”

A decade ago, they received a Lifetime Achievement Grammy; in 2008, the 45th year of their partnership, they received the Ahmet Ertegun Award from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. On May 19, they will be named BMI Icons, given to artists who have a “unique and indelible influence on generations of music makers.”

They spoke about their storied history and their legacy.

Start with the obvious. Is there a song that stands out from your 45 years together?

Huff: “Love Train,” “Backstabbers.” There will always be backstabbers, so people hold onto that one.

Gamble: “Wake Up Everybody,” “Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now,” “Family Reunion.” The songs that are like anthems.

Huff: Ballads … “If You Don’t Know Me By Now,” “Me & Mrs. Jones,” “Love TKO.” “Darlin’ Darlin’ Baby,” by the O’Jays, kills me every time.

The honors have poured in over the last decade for your work. What made Philly International work so well?

Huff: Right there on the third floor there was a big blackboard, and we all knew who was coming into the studio. That closeness of having the studio right there — you wrote a song for Lou Rawls, and you took it right into him. And the competition — me and Gamble were always competing. It helped keep us sharp.

Gamble: There was no boss. The best song wins. That’s the way we always did it. There was also a lot of collaborating, and we attracted writers who liked to collaborate.

So many great songs came out teams working in single studios. We just don’t see that anymore.

Gamble: Collaborations are happening more today than in our time, but what’s different is how the artists today are joining in the songwriting. We always handed an artist a complete song. We’d rehearse it on the spot, but every note was written before we turned it over. We knew what we wanted the record to sound like.

Huff: It was definitely about the details. Our songs were concentrated efforts.

You imported a lot of acts into Philadelphia — the Spinners from Detroit, the O’Jays from Ohio, Lou Rawls from Chicago …

Gamble: We didn’t care where they came from. We flew to Cleveland to see the O’Jays because we heard they had a couple of regional hits, “Lipstick Traces” and “I’ll Be Sweeter Tomorrow (Than I Was Today).” We went to see them at the Uptown. What was unusual was that the acts we worked with were good performers, good live performers.

The fact that you had a house orchestra of 40 musicians must have appealed to some of the performers.

Gamble: And all of those musicians worked as hard as we did.

Huff: When I look back on our records, it’s clear that we were attracting a different, better musician. And they were amazed because once the basic chord structure was done, we allowed them to improvise, to do their thing.

Before Philly, you had already written and produced hits like Dusty Springfield’s “Brand New Me” and “Expressway (To Your Heart).” Then Clive Davis and CBS Records fronted you $75,000 in 1971 to write songs for the new label. By 1974, your had one of the hottest companies in music.

Huff: I always love the way Clive said it: We went on a creative rampage. It exploded. All we needed was an outlet.

Gamble: We had started to heat up and had quite a few top 40 hits. That deal took it to the next level, and we all benefitted. It was good marriage — they handled the administration and marketing.

Leon, you were a studio pianist, but during the entire run of having a label you released only one album …

Huff: It was amazing I even got to do that album. Now I got another one, and it’s got that Phiolly shuffle groove — I was doing that when I was 13. “I Ain’t Jivin’, I’m Jammin” (which appears on 1980‘s “Hear to Create Music”) still packs the dance floor. I’m still into that bop groove, and I think it can get radio airplay — if it’s promoted properly.