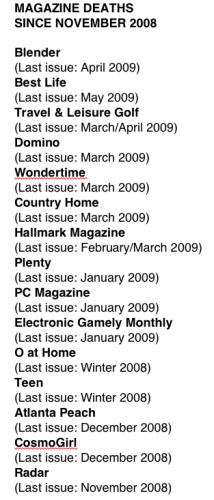

A new kind of memorial is popping up online: a brightly colored tribute to now-defunct magazines. Domino, Best Life and Blender are among the latest high-profile casualties, with a stunning 525 titles dying in 2008, and another 88 this year alone.

But the picture is not as grim for niche magazines. Unexpectedly, the current economy is hiding pockets of success for independent magazines that serve a focused, dedicated subscriber base while keeping their operating costs and advertising rates low.

These may well be titles that most readers glide past on their way to buying the New Yorker or Vanity Fair. But magazines like Drum, EnlightenNext and Road may have something to teach the overstuffed matrons of midtown Manhattan.

These may well be titles that most readers glide past on their way to buying the New Yorker or Vanity Fair. But magazines like Drum, EnlightenNext and Road may have something to teach the overstuffed matrons of midtown Manhattan.

Just as it has on the web, identifying and cultivating a devoted niche audience has worked for certain print products. They are holding up surprisingly well and have no plans to ditch their traditional medium.

“We are stable because our audience is loyal,” said Robert Heinzmann, publisher of EnlightenNext, a "practical spirituality" magazine that started as a newsletter in 1992 and now has a paid circulation of 25,000.

“Over half of our subscribers have been with us for over five years, and we are one of the best-selling titles in our genre at Barnes & Noble, Borders, Whole Foods and other chains,” he added. “We’re also a staple of independent bookstores. So among our subscribers and newsstand buyers, we have many good friends.”

EnlightenNext is weathering a slight advertising loss. “Circulation appears to be fairly stable, and advertising is more challenging, though we still fill our pages,” said Heinzmann.

Carrie Leigh’s Nude magazine, which features fine art nude photography, is actually growing, with a current print run of 80,000, four times its inaugural issue in September 2007. Gary Frischer, the magazine’s spokesperson, attributes it to a combination of new subscribers, larger store orders and Internet presales of individual issues. This has happened as traditional adult magazines like Playboy and Hustler have been shrinking radically.

With Nude, Frischer said, advertising was never a big part of the picture.

“Here is where we either got lucky or our original business plan paid off. When we created Nude, it was to place a quality product in the market,” Frischer said.

“We never counted on advertisers. Now it doesn’t matter to us that the advertisers have fled a large part of the print world.”

Indeed, the lower costs of running small magazines mean they charge advertisers less than their more sprawling competitors do, so advertisers have been more likely to stick around.

Some think smaller magazines have also benefited from the fracturing of the mass audience that used to support a land-grabbing publication like Life magazine, or the now-struggling newsweeklies.

The new indie arts magazine Tar, which releases its second issue this month, considers itself more “an art book of what’s happening in this moment,” editor Evanly Schindler told the New York Times this week. For the second issue, Schindler had to drop ad rates as advertisers balked, but kept the print quality by partnering with an art book company.

By necessity, perhaps, these smaller publications have kept a close eye on their audience rather than ogling deep-pocketed advertisers from the start. As Gabriel Sherman wrote recently in The Big Money, “It’s not that magazines are dying; it’s that magazines that were created solely for advertising or market-share purposes are.”

That’s part of what has been bringing down the big titles. Their demise has become part of the grim media story unfolding every day.

Ad Age’s The Last Page feature is “our continuing farewell to magazines that quit print under pressure from recession and digital media,” while Gawker’s “Great Magazine Die-Off” category adds new items almost every day, and features a colorful collage of defunct-magazine covers.

As the recession shows no sign of ending, smaller magazines are benefiting now from the lower overhead they’ve always had. “Excessive corporate overhead is what’s really punishing big titles these days,” said Simon Dumenco, the media columnist at Advertising Age. “Publishing margins just don’t support the luxe life in Manhattan trophy towers like they used to.”

At independently owned Drum magazine, which has a circulation of 36,000, subscription rates are holding firm and a small advertising loss has not been devastating. “The biggest impact is that we have made cost cuts in production and mailing. We’ve gone to [cheaper] saddle stitching — which I actually love because it lays flat when you try to play the music in the magazine,” said publisher Phil Hood.

For Nude, expensive high quality print is an asset, since the publication’s target readers — photographers, artists, and high-end culture consumers — know the difference. “You cannot fully appreciate fine art photography on the Internet,” Frischman said.

Whether the bigger magazine publishers will take a lesson from their humbler counterparts remains to be seen.

“I do think that there’s a certain sort of group-think to the magazine-publishing industry — and a lot of that has to do with the fact that much of the business is concentrated in New York,” Dumenco said. “There’s an old-school New York way of doing things in publishing — a larded, inefficient, self-congratulatory, self-satisfied way of doing things — that worked for a long time because profit margins were high.”

“Some publishers, though, would rather go down with the ship than switch to a cheaper Scotch or give up town-car service.”