British cinematographer Barry Ackroyd came up in the world of documentaries, which made him an invaluable collaborator for Kathryn Bigelow on “The Hurt Locker,” where the whole point of the camera work is immediacy and naturalism. Shooting on defiantly low-tech Super 16 and covering the action with as many as four cameras at a time, Ackroyd managed to thrust viewers into a stark, chaotic landscape, capturing everything from huge panoramas to the smallest glances.

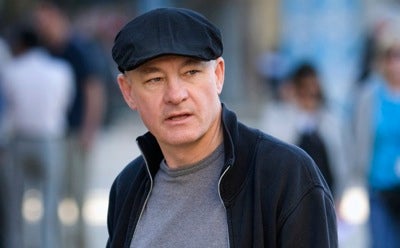

One of the film’s many Oscar nominees, Ackroyd talked about the grueling shoot in a recent phone conversation from London.

(Photo by Jonathan Olley)

Shooting in the Middle East in summer must have brought both creative and physical challenges. Were you aware going in what a tough shoot it was going to be?

Shooting in the Middle East in summer must have brought both creative and physical challenges. Were you aware going in what a tough shoot it was going to be?

Yes, and I think I played a part in the decision to do it that way. Kathryn called me because she’d seen “United 93,” and although that was shot mostly on a sound stage in London, I think she could sense the physical element of it. She said she wanted to shoot in Jordan, as close as we can get to the real place, to make the location a character in the film, really.

And I was more than pleased. I’d done a lot of documentaries, and I knew what the conditions would be like. I realized it would be hot and tough, but that’s part of the filmmaking process if you’re gonna try and get close to the truth.

What appealed to you about the project?

Great script, great director. And it’s the genre that I’ve always liked, and I strive for. In documentaries, we went all around the world to look at and experience things, and then to try to show the world exactly what it’s like to be in this situation.

And this was the same thing. It was exactly like if someone said, “We’re going to make a documentary about the guys who do this work. How do you achieve that?”

So how do you achieve it?

You strip way some of the artifice of making a film. You don’t need crane shots, you don’t need special equipment. What you need is the simplest equipment, and a good eye.

I worked to reduce the technical side right down to its basics. A simple 16-mil camera, sound recording, good design, and all the things that make the thing feel real. And from that you find the story. And Kathryn and I connected very closely on that, even though we didn’t have our first meeting until we got to Jordan.

You might use some documentary techniques, but there have to be significant differences as well.

Of course. That’s the nature of feature filmmaking. The downside is that a feature film can try to get real, but because there’s so much stuff in the way, you can never get completely real. The upside is that in a documentary you might only have one chance to catch every moment, but in a feature film you can have many chances of doing it. So we thought, there’s the advantage, let’s play that up.

How?

How?

One of the many things we did was introduce more cameras, and go for something that’s beyond a documentary. It’s a multiple-camera shoot that gives you multiple perspectives. It can take you from right inside the eye of a character to an overview of the entire scene in a blink, in a move or in a cut. That was a real advantage that we could bring to it.

How many cameras did you use?

It got up to four. It started with two, and we’d have a third camera to come in and do second-unit work. But on a small film like this, where the actors are in every scene, there’s usually no second unit. It ended up that the third camera was much more useful to cover the action. So we’d have a camera in a building, another camera following the guys down the street, another one on a long lens picking up details.

And because we didn’t have a video village around, we didn’t have Winnebagos and tents that we had to hide, we could shoot in 360 degrees when possible. We made the scenes as big and vast and three-dimensional as we could.

But how to you stay out of the way of the actors, and the other cameras?

You set the whole scene beforehand, so everybody knows what they’re gonna do. I operate one camera, so I’ll have my camera at the head of the shoot to cover the main action. And at the same time we’ll have a second camera coming down the street with us, and I just tell him, “You keep me out of your shot, I’ll keep you out of my shot.” Of course the cameras cross, but you can cut that out of the film. And then there’s a third camera somewhere else keeping us both out of his shot.

In any one take, you may have half a dozen frame sizes for anything from three seconds to 30 seconds to four minutes of dialogue, all in one shot. You do that four or five times, you end up with this massive variety of shots, from a close-up on the character’s eye to these big wide shots.

Did you plan every move ahead of time?

No. It doesn’t need a huge plan, I don’t think. It just needs a a kind of attitude. You become a little bit like a character in the film, which is what causes the audience to have a strong personal connection.

Were certain scenes particularly hard to shoot?

The scene inside the car was hard. When they go to the UN building, and there’s a suspicious car, and then it’s on fire … Jeremy and I were inside the car struggling with the imagery. It’s a scene I like a lot, but it was hard. You can see the sweat dripping from Jeremy.

Other times it was hard just to be out in the desert and in the sun, because you tend to overstretch yourself. If you’ve got four cameras, you want to be chatting to them all the time, and I’m not the kind of guy who can walk around with a headset and a walkie talkie. When I want to talk to somebody, I’d rather get over to their position. So it was quite physically tiring.

But you know what, you forget all that stuff. Mostly, I remember it as being a good time. We had a great crew, and we got a great film from it, you know?