Let’s use Peter Jackson’s fabulous “District 9” for a quick and dirty object lesson — or rant, if you like — about Michael Bay, Hollywood’s muddled thinking, and why even the most impulse-driven moviegoers are smarter than anyone thinks.

It’s commonly shared wisdom in Hollywood that familiarity is the new black. Sequelizing, redoing, reissuing, remaking has been the business of the dream factory since the 1980s. Re-peddle what the audience has already bought, supported, and lined up for, the thinking goes, and you’ll laugh all the way to the bank.

It’s commonly shared wisdom in Hollywood that familiarity is the new black. Sequelizing, redoing, reissuing, remaking has been the business of the dream factory since the 1980s. Re-peddle what the audience has already bought, supported, and lined up for, the thinking goes, and you’ll laugh all the way to the bank.

Except that reheating familiarity — like shoving a cold slice of pizza in the microwave — really doesn’t work. At least, it doesn’t work in the way the profit-uber-alles corporations that run Hollywood think it works.

It’s not the familiar that makes money, it’s the imaginative subversion of the familiar. Being playful and knowing about a TV show we all know and love isn’t enough. The movie must be deeply inventive. Profoundly so.

Like the blind pig that occasionally finds the acorn, Michael Bay had a big hit with “Transformers.” Why? Great script. It was an ode to young hearts, to make believe and to boys’ love of the awesome toy. It was about youth and innocence. It wasn’t dumb. It was terrific, sweet and funny.

But the sequel proved that Bay learned nothing from this experience. He reverted to “Pearl Harbor” values: big, loud and dumb on every level, from the sound editing to the acting performances. Sure he made money. But the audience came because they wanted the conceptually impossible — a movie that repeated its own originality.

They didn’t want a second movie just like the first. They wanted a first movie just like the first movie.

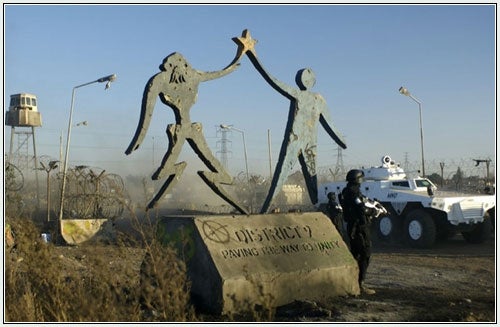

What’s ingenious about “District 9” (co-written and directed by South African born Neill Blomkamp, pictured at right) is the way it cannily appropriates symbols and clichés of the apartheid regime of South Africa — the snarling dogs, the barefoot kids, the depressing shanty houses, the dust, poverty and hopeless — and repurposes them into a stunning sci-fi movie.

It’s our recognition of those symbols that gives the movie heft. We are watching apartheid in parenthesis. And yet, we are seeing it in an entirely different light. Deep stuff.

In the movie, the ones living in the tin shacks are not black Africans but aliens with shrimp-like heads. Their pejorative name: prawns. The back story: They’re refugees from another planet. Their spaceship — almost 30 years before the story opens — arrived above Capetown, and disgorged the lot of them.

Decades later, the spaceship is still hovering there. The aliens are “housed” in the shanty town. They are treated like scum. They have ID cards. And they forage around this hellacious place for their favorite food — canned cat food. Their oppressors are the goons of M.N.U. (Multi-National United), a private military company given to intense surveillance and harassment of the aliens.

Without giving away too much more, the story gets rolling when a human accidentally absorbs alien DNA. In short order he becomes a fugitive on the run and develops a relationship of desperation with one of the prawns’ most subversive elements, a prawn called Christopher Johnson.

(What a name! That’s what some African Americans would mockingly call a slave name. Except he’s an alien from outer space. That’s repurposing the familiar into startling originality.)

Even though the art house crowd will appreciate “District 9,” it’s not esoteric. It uses most of the elements of the blockbuster movie — special effects, a highly mobile camera, hyper-speed editing. It even rolls out that newest of multiplex clichés — the so-called “bromance.” But it puts all these elements into such an original context, you feel as if you’re seeing all them for the first time.

The movie also keeps the right perspective, in terms of narrative and sensation. For all its effects, the movie makes sure the story remains the jockey, and technology remains the horse – not the other way around.

Despite themselves, the impulse-driven, Accutane-popping moviegoers who are the lynchpin of this industry respond accordingly to quality. They get smart movies. They may not be able to articulate why, but they get them.

And thanks to a strong viral ad campaign at Comic-Con, and the fanboy network, this movie has the makings of a hit. Here’s to its deserved success — for all the right reasons.