Dear Justin Bieber:

So here you are, at the top of the world. You just turned 16, you’re a YouTube sensation, and now the first artist to have seven songs from a debut album — which just this week hit No. 1 — on the Billboard pop charts.

You are, pardon the expression, a bona fide teen idol.

But, see, “teen idol” is a tricky thing to pull off – or, more to the point, a tricky thing to recover from. I guess you could say that the other Justin, Mr, Timberlake, has turned the trick nicely, segueing from his days with N*SYNC into a grownup career … but the pop charts are littered with the bones of onetime idols who faded, flamed out, and wound up writing bitter tell-alls or hanging out with Dr. Drew.

Which means that as you sit here on top, it might be time to take note of some of the folks who’ve been here before you.

Herewith, a few lessons you might want to learn from past teen idols:

This is as big as you’re gonna get. That’s OK.

Seems easy so far, doesn’t it? You make videos, mom puts ‘em on YouTube, a record exec sees them and calls you, and the next thing you know you’re making music with Usher and Ludacris.

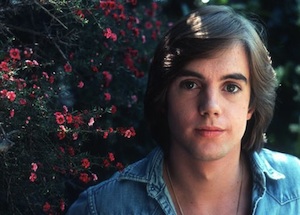

Better open a savings account, because it doesn’t last. Oh, sometimes it lasts for a couple of albums, but eventually it’ll fade. Donny Osmond’s biggest hit was his second one. David Cassidy’s, his first. Shaun Cassidy’s, his first. Leif Garrett’s, his third.

eventually it’ll fade. Donny Osmond’s biggest hit was his second one. David Cassidy’s, his first. Shaun Cassidy’s, his first. Leif Garrett’s, his third.

Take it from Shaun Cassidy, a true teen idol in the ‘70s, now a Hollywood writer-producer: “I was a teen idol and that has a short shelf life,” Cassidy told Suicide Girls. “Having seen my brother David go through it, I knew this was a sort of win-the-lotto kind of thing. Then it’s over and you have to figure out what you want to do.”

It’s never too early to start thinking about how you’ll do it when the numbers are quite so big, or the fans so frenzied.

Don’t try to get too adult, too quickly.

Any teen idol whose music is largely catchy and disposable – and let’s face it, yours is – eventually reaches the point where he or she wants to be seen as a serious, substantial artist. The best way to do this is gradually, the Timberlake way.

Or you could do what David Cassidy did in 1972, when he appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone. The interview talked about his sex life and drug use, and the accompanying photo showed a few tufts of pubic hair.

Outrage ensued – and, Cassidy later wrote in his book “C’mon, Get Happy,” “the new, serious-rock fans I’d hoped to win by speaking frankly in the respected Rolling Stone magazine never materialized.”

His lesson: “the last thing a performer wants to do is lose the audience’s trust.”

You may start to hate your old songs, but make peace with them.

At some point, you might decide that you really don’t like, say, “Baby” and “Favorite Girl." But your fans are still going to want to hear them. They don’t want to hear you patiently explain that you’ve moved on. Part of the reason they go to see you is to revisit that thing that drew them to you in the first place.

Here’s the deal: just like Donny Osmond with “Go Away Little Girl” and Debbie Gibson with “Only in My Dreams,” you’re going to end up reconciling yourself to your old songs. Why torture yourself in the meantime?

On this count, take a lesson from a teen idol who died long before your were born. Ricky Nelson wrote a song about how he hated doing his old songs. And then that song (“Garden Party”) became a hit, and he probably got sick of doing that, too. And by the end of his life, he was doing those old songs he’d spent so many years trying to avoid. And you know, they sounded pretty good.

At some point (but probably not now), get the skeletons out.

Call this the Ricky Martin rule.

As a teenaged singer in Menudo, no way could he come out of the closet and admit he was gay. As a sex-symbol icon singing “Livin’ La Vida Loca,” it would have been awkward. But sometime between then and this week, when he finally acknowledged his “secret,” it had become a kind of common knowledge, and evasion just turned him into a punchline.

I’m not saying that you have anything to reveal. But if you do, don’t wait until it’s too late.

Drugs: definitely not a good idea.

If you’re tired of being seen as squeaky-clean and wholesome, a drug bust or DUI will definitely change your image. But, you know, it’s not really worth it.

I mean, look at Donny Osmond. At one point in the ‘80s, desperate to change his freakishly wholesome image, he hired a publicist who, he said, “figured out this whole campaign to get me busted for drugs and change my image … he said you should start drinking … go to some parties, get some pictures with some booze in your hands. And, you know, I considered it for five minutes.” And decided against it.

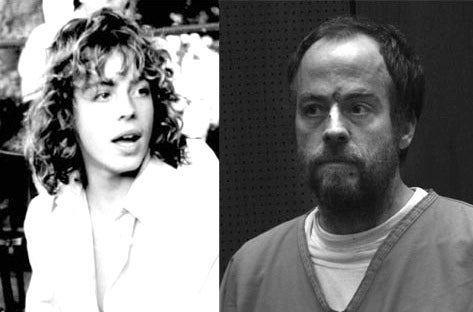

Then there’s Leif Garrett, who got in a car accident while on Quaaludes at the age of 17, had an intervention in the 1990s, but has recently been arrested a few more times for drug-related charges.

Osmond is currently performing nightly in Las Vegas with sister Marie. Garrett has pleaded not guilty to felony drug possession and is awaiting trial. You do the math.

Osmond is currently performing nightly in Las Vegas with sister Marie. Garrett has pleaded not guilty to felony drug possession and is awaiting trial. You do the math.

If things go poorly, just remember: it’s gonna make a great episode of “Behind the Music.”

Let’s face it: the episodes of VH1’s music-doc show that we love are the ones full of triumph and tragedy, wreckage and redemption. So while those rough times might be hell to go through, you can always remind yourself that they’re the reason why Milli Vanilli has a better “Behind the Music” than, say, the Backstreet Boys.

And then there’s the corollary:

If all else fails, there’s always reality TV.

This is the ultimate no-brainer. No matter how wrong things go, no matter how long it’s been since your last hit, you were once Somebody. And reality TV loves former Somebodies. As long as the genre exists – and I get the feeling that long after the Conan wars are over, after every drama and comedy current on the air has run its course, we’ll still be dancing with the biggest bachelor losers in celebrity rehab – you’ll have a home.

In fact, VH1 had a reality show last year devoted entirely to people like you: “Confessions of a Teen Idol,” in which folks like you (only much less famous) attempted to resurrect their careers.

It didn’t exactly work for Christopher Atkins and Adrian Zmed and Jamie Walters and the other participants … but that’s not to say that if you ever need it, reality TV won’t be there for you.

At any rate, those are a few rules laid down by your predecessors. Just in case you don’t pull off this career thing quite as easily as that other Justin.

Good luck, and I’ll see you on VH1.