As Sharon Waxman has pointed out, the Thursday shuttering of Miramax marks the end of an era in independent film, the demise of a company that brought us “the movies that defined the latter part of the 20th century.”

But in the world of awards, the death of Miramax means more than that. Over the past 25 years, no studio has dominated the Oscars the way Miramax did, in ways both good and bad.

Harvey and Bob Weinstein’s company revolutionized awards season, turned Oscar campaigning into a contact sport, infuriated rivals, led to new Academy campaign regulations, caused a change in the Best Picture rules … and, along the way, did a very, very good job of winning Oscar nominations and taking home statuettes.

They landed Oscars for Michael Caine, Daniel Day-Lewis, Quentin Tarantino, Anthony Minghella, Gwyneth Paltrow, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Renee Zellweger, Neil Jordan, Billy Bob Thornton, Matt Damon and Ben Affleck, and many more.

They landed Oscars for Michael Caine, Daniel Day-Lewis, Quentin Tarantino, Anthony Minghella, Gwyneth Paltrow, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Renee Zellweger, Neil Jordan, Billy Bob Thornton, Matt Damon and Ben Affleck, and many more.

Including Roberto Benigni, recipient of what screenwriter William Goldman famously called “the scummiest award in the Academy’s history.”

Miramax pushed the boundaries and reaped the rewards – and if they left disgruntled rivals complaining about their tactics, you’d hardly expect any different when, for instance, an indie company gets as many Oscar nominations as Warner Bros., Universal, 20th Century Fox, Sony and Disney (its parent company) combined, as they did at the 2002 Oscars.

“Miramax has gone at the whole idea of campaigning in a way that just hadn’t been seen before,” said Bruce Davis, the Academy’s executive director, a few years ago. “They see it as a competitive sport, and look for every edge, every angle. And they’re not the only ones responsible, because the others have felt the need to step up and match them.”

In a way, the Weinsteins built their company with awards: landing Oscars for films like “My Left Foot,” “The Crying Game” and “The Piano” gave the company credibility with actors and filmmakers, who saw it as a place that knew how to follow through.

By early 1990s, Miramax had become the most aggressive Oscar campaigner in the game – not only sending out screeners, but hiring consultants and working all aspects of the game. Sometimes they were too aggressive: an overly elaborate package containing the videocassette of “Il Postino” cost them two Oscar tickets when the Academy found it unseemly.

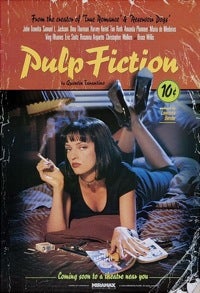

For the 1994 Oscars, the year of Miramax’s “Pulp Fiction,” they won 22 nominations, a dozen more than their new parent company, Disney, and five more than the second-place studio, Paramount. In the Best Supporting Actress and Best Original Screenplay categories, they had four of the five nominees; in Best Director, they had three of the five. (They won in the first two categories, lost in the third.)

Two years later, Miramax won a Best Picture award for “The English Patient,” during a year when four of the five nominees (all but “Jerry Maguire”) were indies, and the prize went to the one that looked least like an indie.

Two years later, Miramax won a Best Picture award for “The English Patient,” during a year when four of the five nominees (all but “Jerry Maguire”) were indies, and the prize went to the one that looked least like an indie.

At the 1997 Oscars, the Miramax film “Good Will Hunting” went head-to-head with a James Cameron juggernaut, “Titanic,” and Harvey Weinstein tried his best to play the gutty little underdog: “If Jim Cameron is saying size matters, then we at Miramax are saying less is more,” he told CNN.

The following year, Miramax came out on top in an epic Oscar battle with DreamWorks. The latter studio’s film, Steven Spielberg’s “Saving Private Ryan,” had been the frontrunner for most of the year, while Miramax positioned its lighter “Shakespeare in Love” as the alternative for those who didn’t feel “Private Ryan” was top-drawer Spielberg.

When writers began pointing out that “Ryan” never quite lived up to the promise of its remarkable opening D-Day sequence, fingers were pointed at Harvey for spreading that angle; when campaign spending reached record levels, DreamWorks chief Jeffrey Katzenberg blamed Harvey.

“There is no question that the extraordinary campaign Miramax has run in support of ‘Shakespeare’ has caused us to do more on behalf of ‘Ryan’ than we had initially planned,” he said to the Los Angeles Times.

After a campaign that was rumored to have cost the two studios as much as $15 million each, “Shakespeare” scored the upset victory. As one of the film’s five credited producers, Harvey Weinstein took the stage and delivered an acceptance speech, whereupon he became the first best-picture winner in years to be played off by the orchestra before he’s finished talking.

Three months later, the Academy’s board of governors passed a new rule that said no more than three producers would be credited on a Best Picture nominee.

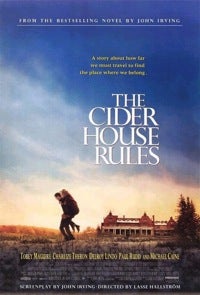

Miramax went head-to-head with DreamWorks again the next year, when Weinstein had “The Cider House Rules” and Katzenberg had “American Beauty.” This time DreamWorks won, after the companies spent so much money that host Billy Crystal turned it into a joke, as he introduced a man who’d been given a reward for finding lost Oscar statuettes.

Miramax went head-to-head with DreamWorks again the next year, when Weinstein had “The Cider House Rules” and Katzenberg had “American Beauty.” This time DreamWorks won, after the companies spent so much money that host Billy Crystal turned it into a joke, as he introduced a man who’d been given a reward for finding lost Oscar statuettes.

“Willie got $50,000 for finding the 52 Oscars,” he said. “Not a lot of money when you realize that Miramax and DreamWorks are spending millions of dollars just to get one.”

That race required some finessing—and, perhaps, some misreprentation – on the part of Miramax.

“American Beauty,” the frontrunner, was tough stuff, dealing with anomie, voyeurism, pedophilia, homosexuality and other undercurrents running through suburbia. So Miramax positioned its film as the safer, more conservative alternative – which required selling it as a love story, and ignoring the fact that Michael Caine’s central character is a doctor who performs abortions and is addicted to sniffing ether.

The campaign worked so well that conservative Republican Trent Lott called it his favorite movie – though a spokesperson, when pressed by Entertainment Weekly, couldn’t say why.

But when director Chuck Workman, who was assembling the Best Picture clips to show on that Oscar telecast, tried to put together a montage that accurately captured the film, he ran into significant opposition.

“Miramax hated what I did, and they screamed at me that it wasn’t the way they wanted to represent the film,” he told me at the time. “It’s my job to show people why the movie was nominated… But they didn’t care about that – they just want us to help their marketing.”

Over the next few years, Miramax landed Best Picture nominations for the likes of “Chocolat” and “In the Bedroom,” but things were relatively quiet on the campaigning front: when a whispering campaign sprang up against “A Beautiful Mind,” that film’s distributor, Universal, went so far as to specifically absolve Miramax of any responsibility.

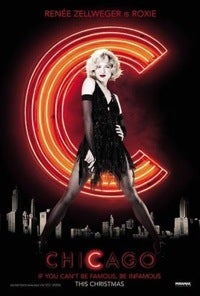

But in early 2003, the company had moments of true Oscar glory, and controversy. When nominations were released, Miramax had 29 for “Chicago,” “Gangs of New York” and “Frida,” and another two for “The Quiet American” and “Hero.” The company also had some foreign rights to “The Hours,” and the Weinsteins had executive-producer credit on Best Picture nominee “The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers.” No other studio was close to their total.

Nominations in the top categories for Rob Marshall’s “Chicago” and Martin Scorsese’s “Gangs of New York” made matters delicate, but Weinstein made no secret of the fact that he was playing favorites in the Best Director race: he wanted to be the man to bring Scorsese his first Oscar.

Nominations in the top categories for Rob Marshall’s “Chicago” and Martin Scorsese’s “Gangs of New York” made matters delicate, but Weinstein made no secret of the fact that he was playing favorites in the Best Director race: he wanted to be the man to bring Scorsese his first Oscar.

Since few people thought “Gangs of New York” was one of the director’s best films, Miramax began to sell the idea that the award would be a de-facto career-achievement award. Central to this was an opinion piece purportedly written by director Robert Wise, who called the film a summation of Scorsese’s work, and said it had his vote.

That by itself caused a fuss – Academy members aren’t supposed to disclose their votes, and Wise was a past AMPAS president – but things got worse when it turned out that the piece had actually been ghost-written by a publicist working for Miramax.

Not only did the ad anger Rob Marshall, according to sources close to the director, but it infuriated the Academy. Miramax said that it had merely been responding to a recent Variety attack by William Goldman – and in the end AMPAS felt powerless to do anything, because the previous year it hadn’t penalized 20th Century Fox for taking out a similar ad – and using Wise – on behalf of “Moulin Rouge” the year before.

“You have to hand it to Harvey,” said Bruce Davis at the time. “He knows every angle, and he knows exactly how much he can get away with.”

Neither Scorsese nor Marshall won the Best Director award that year; Roman Polanski did, for “The Pianist.” But the Miramax film “Chicago” did take home the Best Picture award.

And while Marshall might have been mad at Miramax for a time, he made his latest film, “Nine,” for the Weinstein Company, which the brothers founded after leaving Miramax.

“Nine” doesn’t figure to be much of an Oscar contender this year; Weinstein’s hot contender these days is “Inglourious Basterds,” which landed a SAG ensemble award last weekend.

Then again, would anybody really be surprised if “Nine” popped up among the 10 Best Picture nominees next Tuesday? It is, after all, a Weinstein movie – and when it comes to the Oscars, few people play this game as well as the guys who bought us Miramax.