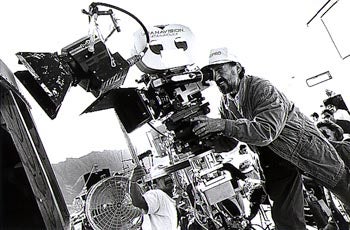

The dazzling light show that served as interplanetary communication in 1977’s “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” helped win both cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond and the film their only Oscar. Zsigmond was nominated three other times as well and won a lifetime achievement award from the ASC for a legendary career that has spanned decades and included multiple collaborations with such directors as Steven Spielberg, Robert Altman, Michael Cimino and Woody Allen. He’s the subject, along with his late friend, colleague and fellow Hungarian émigré Laszlo Kovacs, of “No Subtitles Necessary: Laszlo and Vilmos,” a documentary airing nationwide Tuesday on PBS’ “Independent Lens” and Thursday on KCET in Los Angeles.

Zsigmond spoke with Eric Estrin about Communist Party bosses and Hollywood studio chiefs and how he managed to develop his own unique vision despite them all.

I lived under Communism, under repression, a dictatorship, and everybody is fearing for their life because in the middle of the night somebody can knock on your door and take you away.

I went to work in a factory, and at one point I was complaining to the party secretary that I want to go to the university but they will not take me.

She looked at my file and said, "Oh, you are in big trouble. Your father is in Morocco, in the West; he could be a spy … the only way for you to succeed is to try to show something good for the working class, so that we are feeling that you are part of the working class and you want to help them."

So I was thinking for months and months, "What can I do?" I was a sort of an amateur photographer; I liked to take pictures, so I went over there and said, "How about if I start actually a photography class for the workers and their family members?" And she loved the idea: "That’s great!"

So they set me up with a camera and a developing machine in a little laboratory. So in a year or two I became a hero, and they forgot about my upbringing, you know, my bourgeois parents.

And then they gave me the idea that why don’t they send me up to the film school in Budapest. So I said I didn’t know anything about cinematography. I love movies but I didn’t know how it’s made, but I fell into it.

We had to go through some terrible, hard testing to see if we had talent for cinematography. But I was lucky. From Szeged, where I was born, they had really about 200 applicants, but I was the only one that they took up there.

And then I became a cinematographer after four years of hard study and all that, and then came the Hungarian revolution in 1956, and we were on the streets taking movies, recording all the events. Of course the revolution was beaten down by the Russians in two weeks, and I had to flee from that because of my involvement in shooting the movies. So I decided to leave the country.

I wanted to go to Australia, because that was the furthest away from Communism. But my father came home from Morocco, and he said, "Son, you have to go to Hollywood. That’s the center of filmmaking. If you want to make it, you have to go there."

I honestly didn’t know much about Hollywood at that time. I knew a couple of great American movies like “Citizen Kane” and an English movie, Laurence Olivier’s “Hamlet.” The real movies you could not see. They were blocked off totally from the public.

So I decided to go, basically with my friend Laszlo Kovacs, and that’s how I got into Hollywood — to find out, really, that nobody wanted me. First of all, can you speak English? You have to speak English if you are in America. So I took all kinds of jobs, anything just to support my wife, because I got married to my girlfriend from film school.

And then later on I started to speak English. And then I can make some connections. I can make some low-budget, educational films, you know, with students from UCLA and from USC. And I filmed some documentaries with Wolper Productions. And then slowly, I got more and more work with low-budget filmmakers. I got into making commercials. And then the break came about 10 years later.

I think the first break really was a short-subject film. It was a 30-minute film,

and it was like a little love affair in a supermarket. It was a little story, but beautifully done, and it was nominated for an Academy Award.

By that time, Laszlo did a movie, “Easy Rider,” and that’s how he met Peter Fonda. And when Peter Fonda wanted to make his next movie, “Hired Hand,” Laszlo said, "I cannot do it, but I have a good friend and he’s better than I am."

(If one of us was busy, we’d always say "I cannot do this, but the other one is better." And we never lied, because the other guy really did a good job. And that’s how we helped each other.)

That was really the golden era: The late ’60s and ’70s. We can never see that again because we had all these young directors coming up from nowhere and making these beautiful films with no interference by the studios.

Then I did “Red Sky at Morning,” which was sort of a commercial film. It was very difficult for me to get into it because my director was really a little bit stuffy. He had his own ways to do it; he didn’t really ask for any contribution from me.

It started for me, really, with “McCabe and Mrs. Miller.” My idea was the look of the movie. We were flashing the film and pushing the film. We destroyed the film to the point that it looked like old photographs. That was the whole idea. In those days, you know, Technicolor films were very bright, very colorful, very beautiful. And now we are dealing with a little Western, a Northwestern, and that should look rainy and murky and cold. So we decided to have a very different look than any other movie.

The studio hated it. The studio wanted to fire me, because they said, "Who is this asshole who doesn’t know how to expose the film? It’s terrible! I’ll fire the guy!"

And (Robert) Altman said, "No, no, no, you cannot fire the guy, because he’s very good. Don’t worry about the look of the film because the negative is fine; it’s the print that is bad. In Vancouver where we are, there’s a new lab and they don’t know how to print."

So he cheated, you know? Beginning with that, I did many good films in a row: up and up and up, with better films and better directors.