Documentaries changed my life.

Documentaries changed my life.

By that I mean, after going to film school in Europe, and staying there to work, I began making documentaries that taught me how to make full-length movies, and taught much about the real world around me as well.

The practical lessons I learned in making more than a dozen documentaries shaped my subsequent career as a writer, producer, development executive at HBO and, more recently, as a teacher and head of two universities’ film programs.

Documentaries have changed a lot of other people’s lives, too, and now more than ever. In fact, we’re in a Golden Age for docs, with more distribution outlets, more box office success, more public attention and more talented directors making more meaningful, impactful projects than ever before.

The best documentaries illuminate a person, an event or an issue in powerful ways, giving thousands or even millions of people a chance to better understand something they knew little or nothing about. I would maintain that we’ve never had a greater need for clarity and meaningful discourse than now.

And I’ve returned to making documentaries, like “Cachao: Uno Mas,” which runs Sept. 20 on the PBS "American Masters" series. It’s about the Cuban-born giant of Latin jazz, Israel “Cachao” Lopez, the Father of the Mambo, and a key influence in Cuban and Latin music from his teens in the 1930s until his death in 2008.

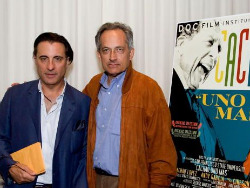

Late in his life, thanks to the support of my co-producer Andy Garcia who produced a number of his recordings, Cachao had a career resurgence that led to multiple Latin Grammy awards, several top-selling Latin jazz albums and world-wide acclaim. Yet he remained little known in Anglo culture, despite having lived in the United States the second half of his long, full life.

The documentary Andy and I produced with Tom Luddy (co-director of the Telluride Film Festival, which this year featured docs by Martin Scorsese, Werner Herzog, Errol Morris, Ken Burns, Charles Ferguson and others) gave me the chance to learn about a superstar in the Spanish-speaking world. I had always loved Afro-Cuban music without knowing much about it. Now I was able to meet and get to know the charismatic man who was a musical genius. Cachao passed on two years ago, but through this film many more people can experience Cachao, his wonderful music and his amazing spirit.

So, documentaries can be a social good too, deepening our understanding of the world around us.

It was with all this in mind that I decided to emphasize documentary making in the curriculum when I took over in July as dean of Loyola Marymount’s School of Film and Television. It’s something I hope to make the signature of the school in years to come.

Documentaries are the perfect place for young filmmakers to begin learning their craft. That’s because fiction film is about re-creating a version of reality, tuned to the story’s dramatic necessities. Documentaries, by contrast, require only that students choose the subject matter and capture what is already there.

That task can be challenging, too, but for beginning film students, it means they don’t have to worry whether the script is any good, or the right person was cast, or if the sets look terrible. They can focus on capturing the images they need, then figuring out the structure and the story in editing (where all documentaries get figured out).

Starting here removes significant roadblocks for students, while giving them a visceral, direct contact with what’s happening in the world around them. They will have begun the process of finding their way to a career of their own, and maybe, just maybe, they can create something along the way that will make a difference in the world.