This story about Edgar Wright first appeared in the Documentary Issue of TheWrap’s awards magazine.

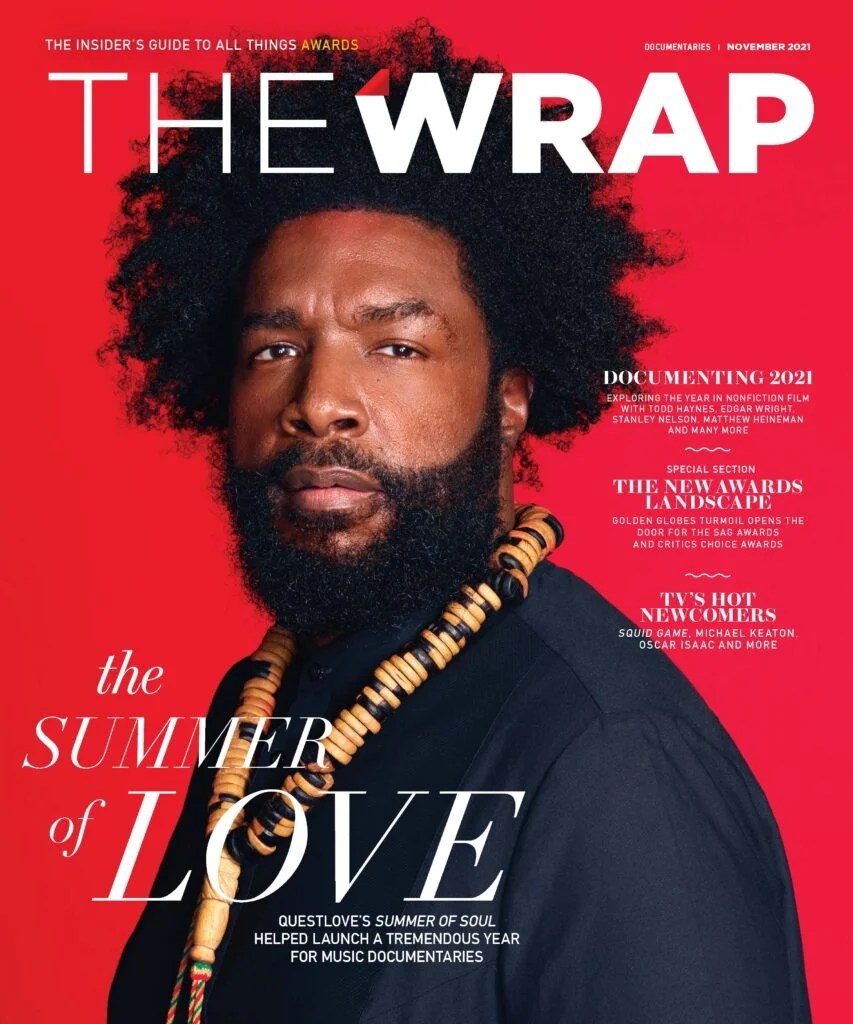

The roster of directors who have made their documentary debut this year is typically long, but also unusual in that it includes a trio of filmmakers who were established in other areas before turning to docs. There’s Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, a star in music and on TV before making “Summer of Soul,” and Todd Haynes, an award-winning director of narrative features who turned to docs with “The Velvet Underground.”

The most novel case, though, may be Edgar Wright, because his documentary debut, “The Sparks Brothers,” overlapped with his new stylish ghost story set in London, “Last Night in Soho.” It’s the kind of twofer that Spike Lee had in 2020 with “Da 5 Bloods” and “David Byrne’s American Utopia,” and Martin Scorsese in 2019 with “The Irishman” and “Rolling Thunder Revue” (though that last film is as much fiction as fact).

“The Sparks Brothers” premiered at Sundance in January and was released in theaters by Focus Features in June, four months before the same company put out “Last Night in Soho.” It gave Wright something of a schizophrenic 2021, and it’s led to days like the one in October when he hung out with the doc community at the Cinema Eye Honors lunch in downtown Los Angeles before being pulled away to do interviews on behalf of Soho across town.

Wright, whose previous films include “Shaun of the Dead,” “Scott Pilgrim vs. the World” and “Baby Driver,” wasn;t really looking to get into the world of nonfiction filmmaking; it’s just that he thought somebody ought to make a movie about the eccentric and influential Ron and Russell Mael, the Los Angeles band Sparks. And then “The Lego Movie” director Phil Lord put it to him that that somebody ought to be Wright himself.

“It wasn’t like I had a to-do list of things I wanted to tackle that included making a documentary,” he said. “I’m a big documentary fan and I particularly love music documentaries.” A grin. “I like watching music documentaries about artists that I don’t really care for — I find those sometimes more fascinating than the people I’m really passionate for.

“But it hadn’t been something that I was necessarily planning on. It was more that as I got to know the Maels, I felt aggrieved on their behalf that nobody had made one. And Phil Lord goaded me into it.”

The resulting film is as playful and as enigmatic as the band, whose 50-year career includes a bewildering variety of styles, flashes of fame and down times. At the beginning of the film, superfan Jason Schwartzman says he doesn’t want to see the movie because he doesn’t want to know too much about Sparks; over the end credits, the Maels deliver a list of untrue facts about themselves.

In between, you’ll learn a lot about the band and their music (but not the Maels’ personal lives) and you’ll hear from a variety of fans who are more famous than Sparks — but you won’t walk away thinking you have figured out the band, because Wright is looking to deliver an experience, not an explanation.

“My pitch to them was that I wanted to cover the whole story,” said Wright, who was told by the brothers that they turned down other directors who’d wanted to focus on the high spots. “I think with Sparks, the troughs are as interesting if not more interesting than the peaks, because they’re character building. And the troughs usually trigger some kind of 180 in style and tone.

“They’ve been a working band for 50 years — they never broke up, and they continued planning their own course without worrying too much about market forces. Over time, that has turned from being something that might seem like a choice to something that seems heroic.”

What struck him the most about the process of making his first documentary, he said, was the amount of work it took to source everything. “My main memory of it was coming to work and watching the archive grow,” he said. And at the same time that was happening, another archive was growing for “Last Night in Soho,” a music-heavy film that slips between current-day London and the Swinging London of the 1960s, and between a drama about an aspiring fashion designer (Thomasin McKenzie) and a horror story about show-business predators and the disappearance of an aspiring singer (Anya Taylor-Joy) half a century earlier.

You could say both of his movies spring from the same well — when Sparks began making music in the 1960s, they were inspired by the Kinks and the Who, both of whom are on the Soho soundtrack, and the darker side of showbiz figures into both stories, though in a far bloodier manner in the narrative film than the doc.

And research, he added, was as important to “Soho” as it was to “Sparks.” “I didn’t want it to be a film about my perception of the decade, I also wanted the reality of it,” he said. “So I researched every single element of what Soho was really like in the ’60s — the criminal element and the sex industry, and also different explanations of paranormal activity, sleep paralysis and other phenomena. I basically had the story, the songs and this phone-book-sized tome of research that was fascinating and harrowing in equal measure.”

Wright said he is haunted by cautionary showbiz stories and intrigued by Soho’s mixture of intoxicating fun and a darker, seedier side. (When he found out that co-writer Krysty Wilson-Cairns lived over a Soho strip club for a while, he knew she was the right person to work with him on a film he’d been thinking about for 10 years.) “There was something about making a movie in that genre that really excited me,” he said. “It was darker than my other movies, not a comedy, but I felt a very deep connection with the city and the story.

“It’s not dissimilar to ‘Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood,’ where I found this profound sadness about the film at the end. Disaster is averted, but then you’re reminded that this is not real life when the credits come up.”

Read more from the Documentary Issue here.