It might be too easy to say that “Restrepo” is the “Hurt Locker” of war documentaries, but Tim Hetherington’s and Sebastian Junger’s Afghanistan-set doc certainly has similarities to Kathryn Bigelow’s Oscar winner. Both films look at current wars by focusing sharply and relentlessly on the day-to-day lives of the soldiers in combat – in the case of “Restrepo,” on the men of a single platoon in the deadly Korengal Valley in Afghanistan.

“Restrepo,” which is going into its second weekend in theaters, won the Grand Jury Prize for documentary at Sundance and seems likely to show up on the Oscar documentary shortlist when that process begins. This is the first feature film for British photojournalist Hetherington and American journalist (and author of “The Perfect Storm”) Junger, both of whom have both done extensive reporting from war zones around the world.

One of the big issues in documentary films these days is advocacy vs. journalism. "Restrepo" is clearly in the journalism camp.

Junger (at left in photo): Well, we wanted to capture the reality of the soldiers. And soldiers don’t talk about the war politically or morally. They really don’t. I think in Vietnam, with the draft army, there would have been a lot more sitting around talking about the war, saying, “What the hell are we doing here?” But here, there wasn’t. These are all volunteers.

Hetherington: People are angry at us for not advocating some kind of political solution in the film, but I think what they actually want is an anti-war political advocacy, a “stop-the-war, this-is-wrong” kind of thing. Nobody’s going to ask us to advocate that the war should keep going. The advocacy is usually a kind of left-leaning, liberal idea.

Junger: And let me be clear, you’re talking to two left-wing, human-rights reporters.

Hetherington: This is a particular strategy we’re using. This focuses on a group of soldiers, because we understand that the best way to get Americans to focus on what’s happening in Afghanistan is by using the example of their own.

Nowadays, making an independent documentary film is so hard that usually, the usual model is that your film becomes a model for advocacy, so you can enlist that support group and get as much juice out of your film as possible. That’s just practically, financially, what you need to do.

So of course it upsets the balance when suddenly you’ve got guys making a film that isn’t an advocacy film, about a subject that’s so charged.

Some of the complaints have also focused on the film never really addressing the larger issues of the war.

Hetherington: There is a lot of political reporting out there. There’s a deluge of books about Afghanistan, there’s a deluge of reporting out there. What there isn’t is a large, contextualized body of work about the experience of war.

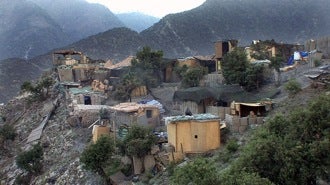

Junger: I’m glad that people are evaluating the war as a whole. But that makes what we did stand out a little bit, because literally, our focus was three miles of a six-mile-long valley. And that was it.

Hetherington: This is a visceral, experiential war film. And we just think there’s a massive need, at this critical juncture, for people to put their politics aside in the lobby of the theater, and go into a dark room for 93 minutes to experience and share what these guys go through, and in some ways digest it and honor it.

Do you ever feel as if having a camera made the soldiers play to it in a way that they wouldn’t if you were just sitting in the corner with a notebook?

Junger: There’s a little bit of awareness, but nothing of real significance. If you turn on a camera in some civil wars in Africa, they’ll be like, “Let’s light up the village!”

Definitely, less professional soldiers will show off for the camera – or they get really angry, and you become in danger because of the camera. But American soldiers are really professional, and they would never violate the rules of engagement for the camera.

Hetherington: The military has a very prickly relationship with the press, and when we turned up the guys were very suspicious of us. But after a while, we started getting close to them, and things went away. So when we did pull out a video camera, it wasn’t a big deal.

How did the two of you hook up?

How did the two of you hook up?

Hetherington: Sebastian had this idea to follow a platoon in Afghanistan, and Vanity Fair teamed us up. We first met in the London airport on the way to Afghanistan, and he’d brought this dilapidated video camera and had a hare-brained scheme to make a documentary. (Laughs) From there, it kind of grew organically.

Junger: I knew I wanted to follow a platoon for a whole deployment, and write a book. And I thought, as long as I’m writing a book, I might as well shoot a lot of video. And I was going to pay for it by doing assignments for Vanity Fair.

I did my first trip in June ’07, I shot video then, but without any instruction. It was completely instinctual shooting, so you can imagine what that looked like. And then Tim and I hooked up for my second trip. Each of us did five one-month trips, sometimes together, sometimes apart, so we did a total of 10 trips between the two of us. And every trip, the documentary became a more and more obvious thing to do. Because the material was incredible, the access was incredible, the story was amazing. It just drew us in.

Hetherington: And in some ways, video, contextualized with sound, is so visceral that it’s the ideal medium to convey this experience.

Were there moments when the focus shifted from the Vanity Fair articles, or Sebastian’s book, or Tim’s photographs, to the film?

Junger: They’re totally complementary. There was no conflict. There were scenes that were much better recorded by a notebook, like a conversation in the dark. And there was other stuff, like firefights, that would have been ridiculous to take notes, that was better with the camera. It all just reinforced itself.

Hetherington: It’s funny, the old media idea is very segmented, like “this is my territory and this is yours.” But media is changing now. You’re at a point now where people can start to move into different forms. I think what makes the project so interesting is that it’s so multi-layered.

He’s written a book [“War”], I have a book coming out in October, we had two "Nightline" pieces, two Vanity Fair articles, I have a set of images that go around the world in an art gallery installation. Each of them have different audiences, and they kind of each elucidate the subject in a slightly different way, and they ping off of each other.

We’re entering this new media sphere where those things kind of work. I think inevitably we’ve reached a point where if I go somewhere, it seems natural that my kit bag is a field recorder, and a video recorder, and a still camera.

Having been in so many arenas of conflict in both your careers, are there things that are specific to Afghanistan that you don’t see anywhere else?

Junger: It’s an exceptionally backwards country. It’s had 30 years of war now, so infrastructure is completely destroyed. Bosnia wasn’t like that. Liberia came close, but it was sort of different. And also, Liberia is not at the center of a massive geopolitical game. Afghanistan is and has always been. The history is dramatic, the politics are dramatic, the landscape is incredibly dramatic. It’s a very intense culture of honor and hospitality, so everything is projected very large on the screen.

How far back do your travels there go?

Junger: I’d been there in ’96 and again in 2000 with [Ahmad Shah] Massoud when his forces were fighting the Taliban. In 2001 I was with his forces when they took Kabul, and I saw the incredible jubilation of the Afghans when they got rid of the Taliban. And then I just saw it fall apart, because the U.S. didn’t put enough soldiers in there.

Talking about “hearts and minds,” we had that in ’01, ’02. They were incredibly grateful, and they hated the Taliban. And then the Bush administration walked away and went to Iraq.

The end titles say that at the end of 2009, the U.S. military started to pull the troops out of the Korengal valley.

Junger: They’re completely out now. They completed the process in April.

In the long run, did the U.S. presence there help?

Junger: Did they help the locals? In some ways yes, and in some ways they made their lives hell. They built a school, they started building a road that they weren’t able to finish. They brought in medical help, particularly for the women and the children who couldn’t leave the valley very easily.

Was it worth it? Probably not. I’m just a civilian, but my understanding is that the big problem was that they didn’t have enough men. They couldn’t do the things they wanted to do in that valley, things that would have been a tangible help to those people, because they only had 150 men. And that’s because there were 500,000 Americans in Iraq.

Does the Taliban control the valley now?

Junger: Yeah. But there are no Americans there now, so they don’t really even need to be there. The Taliban go where the Americans are, to fight them. They’re not in the Korengal right now, because there’s nothing going on.

Jonathan Glickman Named New Miramax CEO